Combating Cancerous Rumours with the Chinese Legacy Media

A graduate research post by Simeon Vonk.

Public opinion, so the quote attributed to Walter Lippmann goes, is merely journalistic opinion. Journalists, according to this view, have the privilege of deciding what is news and get to map the scope of acceptable opinions that can be voiced in the public sphere. This role is called the gatekeeping function.

There have always been good reasons to doubt to what extent journalists truly have the last word on what is newsworthy and what is acceptable to think; consider, for example, the influence of moneyed interests and governments on journalists in both liberal and illiberal states. Nevertheless, the idea that journalists get to shape public opinion was true enough in an era in which the legacy media only faced competition from each other.

The term ‘legacy media’ refers to the mass-media that predate the popularisation of the internet, especially newsprint and television. In my research, I use a rather broad definition of the term; newspapers with digital editions and social media accounts still count as legacy media. Admittedly, this definition has its grey areas. To name one: if a legacy media company acquires an online news outlet but keeps it intact, does this turn said outlet into a part of the legacy media or not? A concrete example of this would be the purchase of the contrarian Dutch blog Geenstijl.nl by Telegraaf Media Group. I would love to read your take on this in the comments below.

While rumours of the legacy media’s death (which have been surfacing since the 1990’s) are probably exaggerated, expensive studios and editorial offices are no longer required to broadcast a message to the public at large. ‘Do not hate the media, be the media’ is not an idealistic statement anymore, it is something anyone with an internet connection can put into action. The legacy media have lost their monopoly on the means of producing news and public opinion.

In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), this is bad news not only for the legacy media themselves, but also for the Chinese Communist Party. The Chinese legacy media are supposed to be the eyes and ears of the Party. If they lose control over public opinion and the narrative of current events, then so does the Party. Therefore it should come as no surprise that the PRC government and legacy media have joined forces to discredit alternative sources of news and make people suspicious of what they read on the internet. Their frame of choice is to raise concern over the spread of what they call ‘internet rumours’ (网络谣言).

In my research paper, I will discuss how the Chinese legacy media join forces with law enforcement to combat online rumours and punish those who spread them. In doing so, I will focus especially on articles published since September 2017 on the rumour-busting (辟谣) section of Beijing-based news outlet Qianlong.com. The rumour-busting section’s main page displays an impressive ensemble of allies in the struggle against online rumours. It includes government agencies as well as news outlets and internet platforms:

Cancerous Rumours about Noncarcinogenic Food

Before studying the articles on Qianlong, I took a close look at Chinese academic literature. One of the things that caught my eye was the discourse of infectious disease. For example: in a 2017 article, Gu Jinxi compares rumours to a disease that spares neither male nor female, old nor young, rich nor poor, aristocrat nor commoner. Without better knowledge, one would assume this is about the Black Death. Equally surprising was Yan Fuchang’s use of the term ‘domino effect’ when discussing the influence of internet rumours on the Arab Spring in his 2016 monograph on internet rumours. Since the notion of revolutionary regime change being subject to a domino effect is often dismissed as a delusion of Cold War warriors west of the Berlin Wall, a Chinese academic book was the last place where I expected to find it.

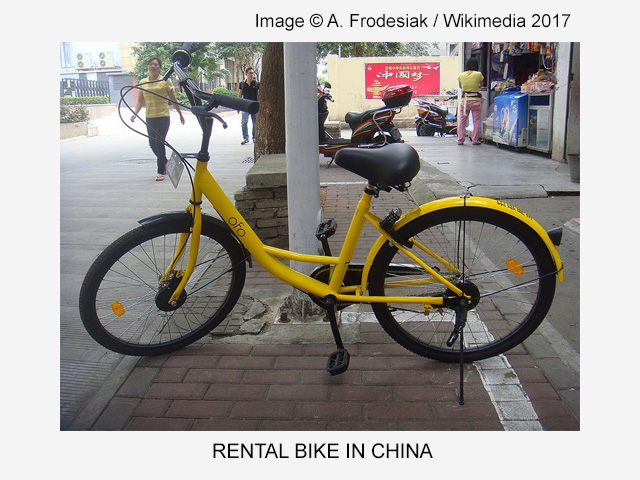

Regime change and the domino effect are not common subjects on the rumour-busting section of Qianlong. Diseases, on the other hand, certainly are. Several articles deal with cancer in one way or another. Whole articles are dedicated to refuting the rumours that crab meat and a vegetable called yuxingcao are carcinogenic. In an item dedicated to refuting rumours about common fruits, an expert explains that eating lemons does not prevent cancer. Cancer is not the only lethal illness featured on Qianlong. A different disease appears in a rather propagandistic piece about the ‘encirclement and annihilation’ of internet rumours. This article featured a bizarre rumour about syringes containing the HIV virus being concealed in seats of rental bicycles of the kind pictured below:

The trolls responsible for spreading this piece of ‘fake news’ (虚假消息) were detained for nine days. In the same article, rumours are described as a big malignant tumour on the internet. This entry, featuring such strong language and a rather extreme and tabloidesque rumour, to my surprise, was originally published in Legal Daily (法制日报), a publication for jurists.

I have yet to lay my finger on the reason why infectious and lethal diseases are common themes in Chinese academic literature on rumours as well as on Qianlong. Prevalence of infectious illnesses has been found to increase support for authoritarianism, but it is a bit of a stretch to assume this also works on a metaphorical or strictly perceptual level (and corroborating or falsifying such a hypothesis is beyond the scope of this project). The China’s legacy media’s message to rumourmongers, on the other hand, could not be clearer: ‘you are the cancer, we are the chemo’.