Censorship Is Not Just Something Uniquely Chinese

A Comparison Between Censorship on Sina Weibo and Facebook

Graduate research post by Vincent Brussee.

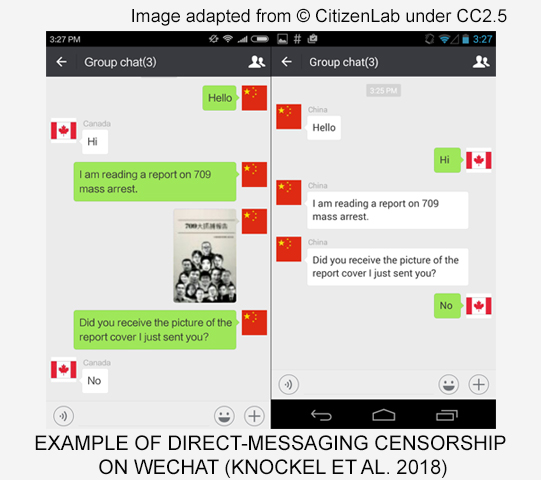

If the early 21st century was heralded as the internet age, in many countries today this seems to be replaced by the censorship age. Today, censorship software is even installed in mobile games, images can be automatically removed on direct messaging apps such as WeChat (see the figure below), and group chat moderators and admins can be held legally responsible for the content appearing in their group chats (source, in Chinese). But make no mistake, this is not merely a trend in China. It happens all over the world, even in your country. Yet, academic research appears to rarely discuss this.

In a thought-provoking article titled ‘Blogging Alone‘, China scholar James Leibold highlights the persistence of ‘digital Orientalism’: the perverse focus on the political implications of the internet in China, while such political implications are rarely focused upon in studies on the internet in the ‘West’[1]. In other words, Western scholars have long asked what the impact of the internet on democracy in China (or the whole of Asia) could be, but they have not asked the same question for their own countries.

It appears to me as if this stems from the idea that censorship is something that just does not happen ‘here’, but that is a grave misconception. Facebook has recently been accused of censorship, been forced by the German government to censor ‘hate speech‘, and stirred up controversy by removing the iconic photo of the ‘Napalm Girl‘ for its nudity. In short, censorship is not just something ‘Chinese’ or ‘foreign’, it is a topic that matters to all of us. Thus, in this blog post I will outline a number of potential ways through which censorship is prevalent on the social media platform Facebook by comparing its censorship guidelines to those of its Chinese counterpart: the microblogging platform Sina Weibo. The result is a tentative and provocative view on censorship in Western societies.

What is censorship?

However, I should first explain what censorship actually entails. Interestingly enough, although censorship is widely discussed, it is only seldom defined by researchers. When I use the term censorship in this blog, I mostly refer to the removal of a piece of information – i.e. (parts of) a message or post – by the medium, so that it does not reach the intended receiver. This definition is by no means fool-proof but covers what is commonly understood by the term. However, it should be noted that censorship does not always need to entail the blunt removal of information. Instead, Facebook states that it does not remove posts it deems ‘false news’, but uses algorithms to make this information appear further down in someone’s news feed. This achieves the same goal: the information will not reach the intended receivers (or at least fewer of them).

Similarities between Sina Weibo and Facebook

This brings me to the first point in which censorship on Facebook can be directly compared to Sina Weibo: the role of the platform. In older censorship systems, the government would be the one to directly impose censorship, i.e. by simply denying access to the respective piece of information (see for example Deibert et al., “Access Controlled”). Nowadays, the platforms themselves are held legally liable for the content on the platforms by their respective governments. Both in the case of Sina Weibo and Facebook, these platforms have hired sizeable amounts of staff in charge of moderating the content on their websites. However, the consequence is potentially alarming: because the platforms want to avoid receiving large fines (up to €50m per case for Facebook in Germany), they will potentially over-censor pieces of information that fall within a ‘grey area’.

This is made further problematic by the vague language that both Facebook and Sina Weibo use. For instance, the Sina Weibo user agreement (in Chinese, article 4.10) states that ‘the image of all levels of national organs and government shall not be harmed in any way (得以任何方式损害各级国家机关及政府形象)’. However, what is really meant by ‘harm’ and ‘image’? This leaves a lot of room for interpretation, because what exactly harms the image of the government? Would any form of criticism harm this image, or would something more ‘severe’ be necessary?

Facebook in many cases does make clear what it understands as forbidden content. For instance, one of its definitions of ‘hate speech‘ is an expression of contempt against a certain person or group of people on the basis of shared racial, religious, ethnic, etc. characteristics. The regulations even state that ‘I don’t like X’ would be a violation. Nevertheless, what if a politician says, ‘I don’t like Christians because I think their religion is violent’? According to the guidelines, this politician’s post would be removed, yet we still regularly see politicians uttering these kinds of statements on social media – just swapping ‘Christians’ for ‘Muslims’. Removing it would be a significant strain on freedom of expression, and Facebook does not appear quite certain how it should deal with this. Similarly, Facebook fails to even define what it considers ‘false news‘ in the first place. The consequence is that this increases that grey area: there are simply more posts where the platform is uncertain whether it is alright or not to leave them online.

Further questions

There are more questions we should ask. Why is China’s recent real name registration system (as also active on Weibo) considered a ‘crackdown on internet freedom‘, while Facebook has had this policy for years? Should we consider algorithms that determine what ends up in our news feed a form of (potential) censorship? Are governments the only ones imposing censorship, or are other actors also capable of imposing censorship? These questions are too much for me to answer in-depth, yet I do want to give a tentative answer to the third question.

In 2016, video platform YouTube was the subject of a backlash concerning its new ‘advertiser friendly‘ guidelines. In short, videos with violent or sexual content or that included sensitive subjects were ‘demonetised’, meaning creators could not earn money off of them, effectively forcing many to adjust their videos. I would argue this is also a form of censorship, and it has been suggested this form of censorship is also present on Facebook. Indeed, would advertisers really want to post ads on politically heated discussions? This might cause their brand more harm than good.

Thus, we should not consider censorship as something that only occurs in authoritarian states, or that is only implemented by states in the first place. Instead, we should take these questions about China and ask them all around the world – only then can we fully understand the impact of the internet on our societies.

Resources

If you are interested in learning more about this subject, the full research paper is available here:

Brussee, Vincent (2019), ‘Comparing Censorship Regulations of Sina Weibo and Facebook’. Research Paper for the Graduate Course The Politics of Digital East Asia. Leiden: Leiden University.

The figure above is from the following online study:

Knockel, Jeffrey, Ruan, Lotus, Crete-Nishihata, Masashi, & Deibert, Ron (2018, August 14), ‘(Can’t) Picture This: An Analysis of Image Filtering on WeChat Moments. Toronto: The CitizenLab.

Notes

[1] Wording from original. The dichotomy between the “West” and “China” is a problematic one, but it is beyond the point of this blog to deconstruct this. In the remainder of this blog, I will use the “West” to discuss English-language scholars/platforms/media/etc. based in the United States, Canada, Western-Europe, and Oceania.