Where Is Digital Asia?

Introduction to the Second Special Issue of Asiascape: Digital Asia

During the launch conference for this journal in early 2014, our editorial team issued a provocation. We asked the participants of that event to answer the question ‘where is Digital Asia?’ Our intention was to see where the growing group of scholars who research digital media in or from the Asian region locate themselves and their work, to specify or to problematize the terms of their inquiries, and to take a stand on the significance of their work. Does it make sense to talk about ‘Digital Asia’ and, if so, where should we look for it? Indeed, is it something that we can look for?

These are some of the responses we received:

‘Digital Asia is global, just as the many populations and individuals identifying as Asian can themselves now be found in locations across the globe.’

‘I would like to take “Digital Asia” as Asia itself, for digital technology is increasingly becoming an integrated part of everyday life in Asia.’

‘Digital Asia is Asia in transformation – politically, socially, culturally, and also legally – by its digital media.’

‘It lies in a combination of the highly local, specific, and personal, and the broad and universal. Thus, it can transcend traditional barriers of nation and state.’

‘Digital Asia is both online and offline, including both digital technologies’ effects on Asia and Asia’s effects on digital technologies.’

‘Digital Asia is so many things that it’s difficult to say it’s anything at all; is there a digital Europe?’

‘Digital Asia is a science fictional creation – we find it in literature, not in the material world.’

As these responses suggest, asking where we might find ‘Digital Asia’ is not simply a question of where Asia might be located geographically, or what role digital media might play in that geographical region. What counts as ‘Asia’ is already a matter of complicated identity politics and knowledge construction, often closely linked to assumptions about the differences between ‘East’ and ‘West’. In some cases, we might find ‘Asia’ in the social processes of a specific locale, be it in a part of India, Japan, or Vietnam. In other cases, we might trace cultural practices to communities of people who see themselves as having ties to Asia, but who happen to live and work outside of the region. In yet other cases, we might examine ideas and discourses about, or imaginations of, ‘Asia’ – regardless of whether they are circulating through Abuja, Buenos Aires, Kuala Lumpur, Ottawa, or The Hague.

What distinguishes good scholarship on an ‘area’ such as Asia is that it challenges our own sense of the location of our work, and that it takes the locations of others seriously. These locations may be situated in specific geographical locales; but, more importantly, they are part of ideological, social, historical, economic, and political ‘places’, which deserve scholarly attention. Writing about China, Van Crevel (2013, 256) points out that a crucial aspect of Area Studies in the twenty-first century is to explore our own positionality: we need to ‘ask about consciously and unconsciously assumed perspectives, images of “self” and “other”, and above all the situatedness of scholarship (researcher, data, theory, method, institutional and socio-cultural context). Where is here?’

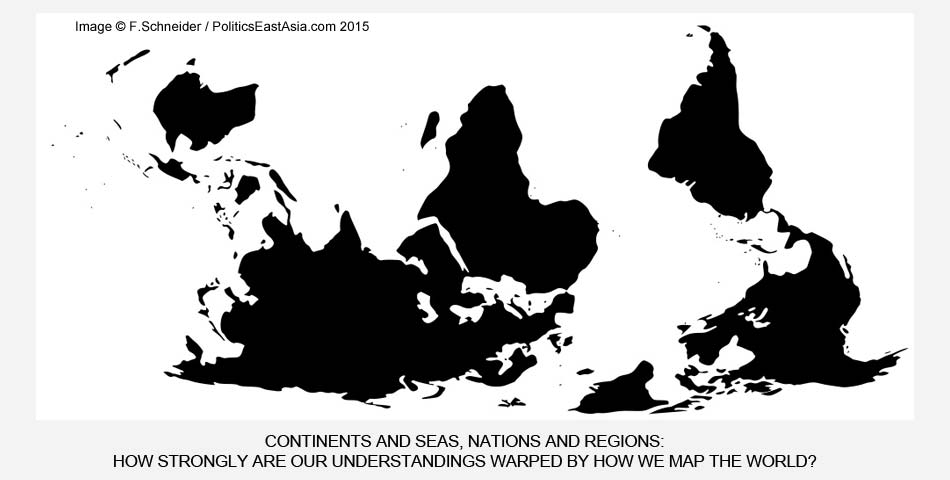

An increasing number of scholars in Area Studies have expressed similar sentiments about how we construct knowledge of geographical areas (cf. the contributions in Wesley-Smith & Goss 2010). Following criticism that such endeavours were complicit in reproducing the Orientalist views of nineteenth-century European imperialism, and later the Cold War politics of the twentieth century (Cumings 1998, 2014), scholars have increasingly used the diversity of their field to infuse Area Studies with a critical angle: one that challenged the idea that the world can be demarcated into geographically and culturally distinct ‘regions’, and that instead asked how such demarcations come about, what they mean to different people in different contexts, and who benefits from asserting them. In this, area scholarship has taken cues from critical geographers like Henri Lefebvre (1974/1991) or David Harvey (2006), and it is in that vein that anthropologist Neil Smith reminds us that ‘the convenience of the area categories is not innocent, as it structures knowledge in specific ways and emanates from specific ideological resonances’ (2010: 36).

Yet, the title of our journal is not only provocative because of the term ‘Asia’. It also forces us to address the meaning of the ‘digital’ – a category that is equally contested. On the one hand, creators and users alike often celebrate digital technologies as harbingers of progress and freedom, while at the same time obscuring that this allegedly universal view of technology has its roots in the neoliberal teleology of California’s tech industry (Marwick 2013; Morozov 2013; Turner 2008). On the other hand, the hopes and fears that digital technology elicit are intricately linked to how scholarship and popular culture imagine ‘Asia’ – whether as a ‘backward’ place that needs to be ‘opened-up’ through ‘cutting edge’ information technologies, or as a hyper-modern, techno-Orientalist dystopias (cf. the critiques in Lewis 2010: 46 and Ueno 1996, respectively). Studying ‘Digital Asia’ therefore also means critically engaging with such fantasies of hyper-dynamic Asian techno societies.

In this special issue of Asiascape: Digital Asia, we have thus asked leading scholars in the arts, humanities, and social sciences to take a critical look at our journal’s title and the research programme it implies. Where do we find the digital in and from Asia? Where does Digital Asia start, where does it end? How do the categories of Asia and Digital interact – where do they intersect? What counts as method in the study of ‘Digital Asia’, and what counts as data? In short, what is the subject and object of inquiry and what methodologies are appropriate for their study?

Our special issue starts with a position paper by historian Prasenjit Duara on how to rethink Area Studies in an age in which the environments we inhabit are influenced by complex human activities more than by any other single force. In Duara’s view, we need to redefine the locus of academic work by moving away from the kind of methodological nationalism (Beck 2005) that commonly defines research in and on ‘areas’. Instead, as Duara argues, scholarship needs to focus on regional networks, particularly if it hopes to address the problems with which humanity is confronted today. Only by taking the challenge of truly transnational scholarship seriously can area knowledge contribute to a ‘sustainable modernity’. For Duara, digital technology can aid such an agenda by changing how researchers trace transnational processes through recourse to big data, but also by empowering actors that do not fall under the purview of traditional nation-states, such as grassroots civil-society organizations.

In the second contribution to this issue, Chris Goto-Jones discusses to what extent ‘Digital Asia’ can fruitfully be connected with the discourse of techno-Orientalism. Using the example of the videogame as an instance of a digital location that can be visited and explored, he suggests that the gamic quality of interactivity adds a new, experiential dimension to the ideological structure of (techno-)Orientalism. Goto-Jones locates this dimension, which he calls ‘Gamic Orientalism’, in the ‘digital dōjō’ of martial arts videogames, where gamers represent their engagement with ‘Digital Asia’ in a manner that echoes the way martial artists talk about the significance of their art as self-cultivation. Illustrated with texts from the bushidō canon and interviews with gamers, the article playfully experiments with the possibility of ‘virtual bushidō’ as the ultimate expression of Gamic Orientalism, suggesting that ‘Digital Asia’ is finally located in an ideologically conditioned mode of engagement with the digital medium rather than in any cartographically defined space.

In my own contribution to this special issue, I ask whether we might find ‘Digital Asia’ in its networks, interfaces, and media contents, and what kind of tools are available to researchers who hope to explore ‘Digital Asia’ by ‘following the medium’. Using the example of higher education institutions in Beijing, Hong Kong, and Taipei, the article examines how search engines, institutional homepages, and hyperlink networks provide access into the workings and representations of academia online. The study finds that even a seemingly cosmopolitan endeavour such as academia exists in rather parochial digital spheres, and that users that enter those spheres do so in highly biased ways – a finding that raises questions about the potential for truly transnational collaborative activities of the kind that Duara envisions in his position paper. Further reviewing the digital tools that lead to these findings, I argue that while digital methods promise to bring together the ‘digital turn’ and the ‘spatial turn’ in the humanities and social sciences, they also pose new challenges. These include theoretical concerns, like the risk to implicitly reproduce views of neoliberal modernity, but also practical concerns related to digital proficiencies.

Returning to the Japanese context, Thomas Lamarre explores the meaning of ‘Digital Asia’ by examining how a particular cultural format has been disseminated throughout the region: the highly popular franchise Hana yori dango, or ‘Boys and Flowers’. Lamarre shows how this series has been formatted both across media forms (such as manga, animated TV series, animated films, television dramas, and theatrical releases) and across nations (Japan, Taiwan, Korea, China, and the Philippines). The case leads Lamarre to ask what happens when production of media networks and media devices or platforms outstrips the production of contents, as is the case in East Asia. To Lamarre, the sense of ‘media regionalism’ that formats like Hana yori dango elicit, stems from structures of feelings that are related both to the gap between infrastructures (of distribution and production) and the gap within media distribution itself (i.e. between mobility and privatization).

Concluding this special issue, Javier Cha finds a paradox: mainstream South Korean academia is still struggling to make sense of the digital turn, despite the fact that high-quality digital infrastructures and sources are widely available. While South Korea’s government continues its aggressive push for more digitized information, academics in fields like history, literature, or philosophy have not been successful at establishing the sort of ‘digital humanities’ initiatives that have emerged elsewhere in the world. Cha argues provocatively that this indifference to the digital reflects a long-standing ‘digital/humanities divide’ that has its origin in the 1980s, when government and business leaders designed South Korea’s transition to a post-industrial society without input from humanists. This legacy, so Cha argues, needs to be overcome if humanities scholars hope to shape the paradigms according to which digital Korea develops in the future.

As all of these contributions show, exploring ‘Asia’ through the lens of digital media and digital developments is a fruitful way to integrate the ‘digital turn’ with the spirit of critical Area Studies – a spirit that aims to challenge the comfort zones of mainstream scholarship. For researchers of ‘Digital Asia’, this means breaking through techno-Orientalist assumptions, but it also means exploring innovative methods and theories. Our contributors have brought their individual perspectives and expertise to bear on the theme of this special issue: ‘Where is Digital Asia?’, and they each have problematized the potentially complex political charge of our journal’s title in ways that we hope will provoke a continuous academic exchange over the meaning of ‘Digital Asia’.

Publishing note: this introduction was adapted for the web from the print version, co-authored with Chris Goto-Jones. All special issue contributions are available, open access, upon registration with the journal Asiascape: Digital Asia. Thanks to Brill’s ‘green publishing’ policy, the journal version of this introduction is also available directly here on Florian Schneider‘s website PoliticsEastAsia.com.

References

Dirlik, Arif (2010), ‘Asian Pacific Studies in an Age of Global Modernity’. In: Terence Wesley-Smith & Jon Goss (eds.): Remaking Area Studies: Teaching and Learning Across Asia and the Pacific. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press (pp. 5-23).

Beck, Ulrich (2005), Power in the Global Age. Cambridge & Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Cha, Javier (2015), ‘Digital / Humanities: New Media and Old Ways in South Korea’. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 2(1/2), 127-148.

Duara, Prasenjit (2015), ‘The Agenda of Asian Studies and Digital Media in the Anthropocene’. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 2(1/2), 11-19.

Goto-Jones, Chris (2015), ‘Playing with Being in Digital Asia: Gamic Orientalism and the Virtual Dōjō’. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 2(1/2), 20-56.

Harvey, David (2006), ‘Space as a Key Word’. Spaces of global Capitalism – Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. London & New York: Verso (pp. 191-148).

Lamarre, Thomas (2015), ‘Regional TV: Affective Media Geographies’. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 2(1/2), 93-126.

Lefebvre (1974/1991), The Production of Space. Malden, MA et al.: Blackwell.

Lewis, Martin (2010), ‘Locating Asia Pacific: The Politics and Practice of Global Division’. In: Terence Wesley-Smith & Jon Goss (eds.), Remaking Area Studies: Teaching and Learning Across Asia and the Pacific. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press (pp. 41-66).

Marwick, Alice E. (2013), Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age (Kindle ed.). New Haven, CT & London: Yale University Press.

Morozov, Evgeny (2013), To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems that Don’t Exist (Kindle ed.). New York et al.: Penguin Press.

Schneider, Florian (2015), ‘Searching for ‘Digital Asia’ in its Networks: Where the Spatial Turn Meets the Digital Turn’. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 2(1/2), 57-92.

Smith, Neil (2010), ‘Remapping Area Knowledge: Beyond Global/Local’. In: Wesley- Terence Smith & Jon Goss (eds.), Remaking Area Studies: Teaching and Learning Across Asia and the Pacific. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press (pp. 24-40).

Turner, Fred (2008), From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Ueno, Toshiya (1996), ‘Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism: Japan as the Sub-Empire of Signs’, Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, Documentary Box #9. Retrieved 20 August 2014 from: http://www.yidff.jp/docbox/9/box9-1-e.html.

Van Crevel, Maghiel (2013), ‘China Awareness, Area Studies, High School Chinese: Here to Stay, and Looking Forward’. In: Wilt L. Idema (ed.), Chinese Studies in the Netherlands: Past, Present and Future. Leiden: Brill.

Share This Post, Choose Your Platform!

One Comment

Comments are closed.

[…] This research was made possible with the generous support of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), through a VENI grant for the project ‘Digital Nationalism in China’ (grant 016.134.054). The article is part of the 2015 special issue of Asiascape: Digital Asia that deals with the question: “Where is Digital Asia?” […]